Submit to the Governing Authority?

Processing some thoughts as I research Romans 13:1-7

My thoughts today will be brief and perhaps a bit more all over the place than normal.

I’m currently taking a class co-taught by Tim Gombis and Nijay Gupta on New Testament Letters and Revelation. My research paper for this class is asking the question, “What did Paul mean by Romans 13:1-7?”

For those not immediately familiar with what I’m referring to, it is the text reads as follows:

Everyone must submit to governing authorities. For all authority comes from God, and those in positions of authority have been placed there by God. 2 So anyone who rebels against authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and they will be punished. 3 For the authorities do not strike fear in people who are doing right, but in those who are doing wrong. Would you like to live without fear of the authorities? Do what is right, and they will honor you. 4 The authorities are God’s servants, sent for your good. But if you are doing wrong, of course you should be afraid, for they have the power to punish you. They are God’s servants, sent for the very purpose of punishing those who do what is wrong. 5 So you must submit to them, not only to avoid punishment, but also to keep a clear conscience.

6 Pay your taxes, too, for these same reasons. For government workers need to be paid. They are serving God in what they do. 7 Give to everyone what you owe them: Pay your taxes and government fees to those who collect them, and give respect and honor to those who are in authority. (New Living Translation)

Perhaps sometime after I the paper is finished (and my work not deemed insane) I’ll share it in a later post. For now, I offer a few simple reflections and questions I’m thinking through on some of the key issues surfacing as I research the text.

Here are three in particular that I’m noticing.

1. A Complicated History

Beverly Gaventa put it best when she said, “we always read with our interpretive predecessors.”1 Indeed the interpretive history of this passage has been used even recently by government leaders as a call for quiet obedience to laws that would be dubious for Christians to follow.2 Yet interpretive history of this passage is not so straightforward as “do what your local government tells you.”

The early church fathers such as Origen and Polycarp saw this as a passage with limited scope and always subject to the greater issue of obedience to God and the way of Jesus.3 Origen is downright troubled by Paul’s suggestion that government officials are God’s judges!

The tone is markedly different for the likes of Calvin and Luther who see, in different ways this government as sanctioned by God.

One early consideration and observation I am finding as I read is that there is a distinctly different tone in interpretation Pre-Constantine and Post-Constantine. Meaning, those who experienced persecution and lived life on the margins seem to interpret this passage with very limited license for government officials vs. those who experienced the governments favor upon the church.

So one of the big questions I’m considering is how does this interpretive history affect how we read Paul’s words to his original audience? How much scope did Paul really intend for the Roman church to give government officials in their lives and actions? What limits did it have or not have?

2. The Church and the State?

Many interpretations in relatively recent history view this passage as a relationship of the Church or the Christian to “the State.”4 Yet this idea or concept of “the State” appears no where in this section, hence why above I’ve used the term “government officials” since that is the term used by Paul here. Quite often when Romans 13 is invoked in the modern world, the interpretive history reads “the State” into the passage in a way that demands blind loyalty to the entire structure and shape of the governing institution.

This has produced dangerous theologies in which, in Nazi Germany for example, the German evangelical church saw itself as required to obey the legal laws put in place by Hitler’s regime, whether or not they were appropriate for a Christian to follow.

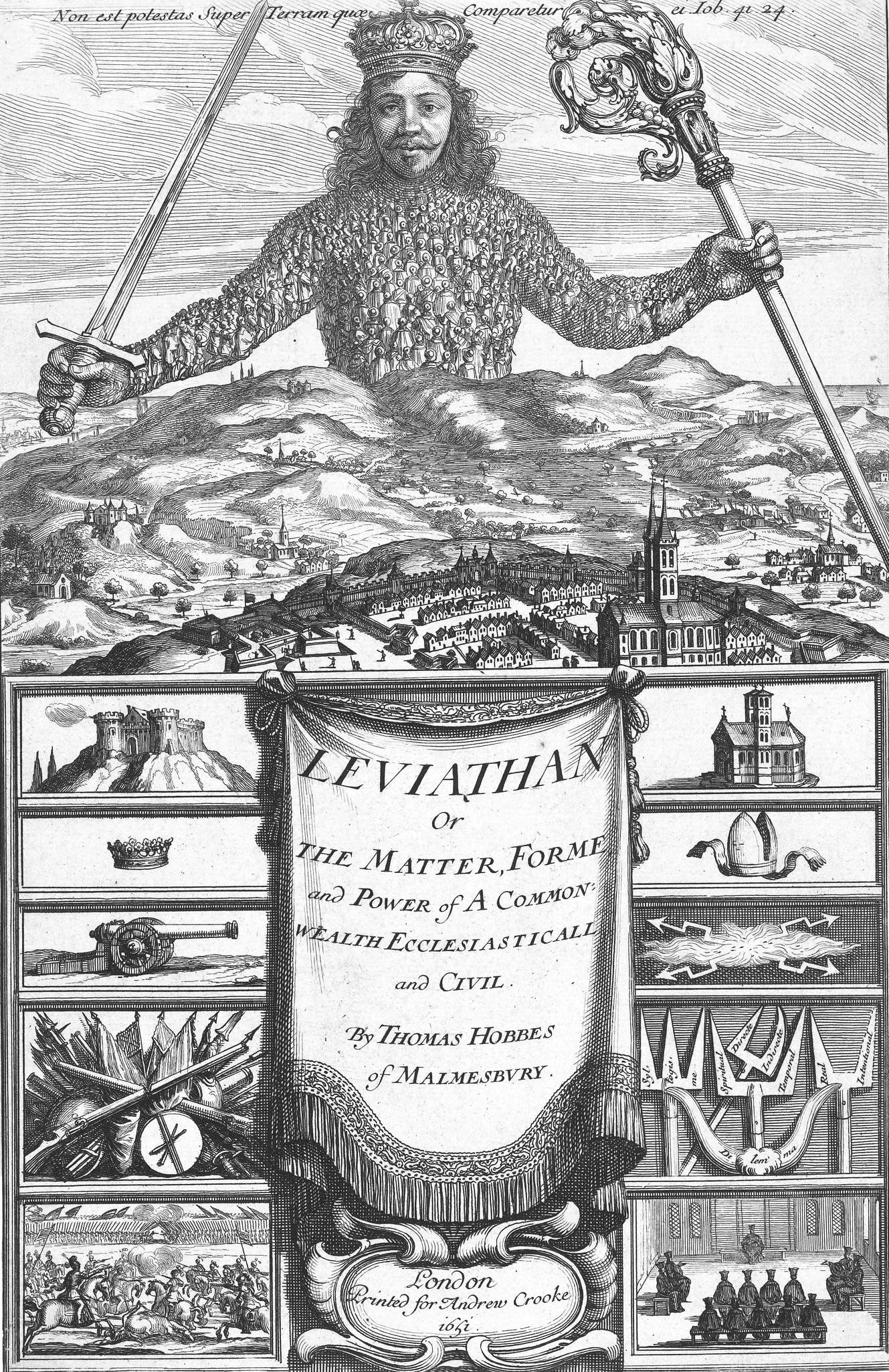

The over-reading of “the State” here is certainly inappropriate as, one the one hand that is a much more modern concept akin to Hobbes Leviathan, where the people of a particular ethnic-cultural group have been joined together into a singular body with the prince as the head.

Instead, Joseph Fitzmeyer and others, point out that the greek word is very limited here and simply refers to individual, generic, government officials.5 Likely, we are talking about government officials in a municipal or regional capacity, and probably, those who specifically collected taxes.

The question here is how does one untangle our modern interpretations of “the State” from the text and read Paul appropriately in context.

3. Submit?

The final thought I’ll offer here in this scatter-brained post is around the word “submit”.

Submit is often taken as a very strong word and the use of it in relationship to government officials may cause one to question how far to take this command from Paul. Indeed as already mentioned, those who experienced persecution at the hands of government officials in the early years of the church, and indeed those who experience government sanctioned persecution and marginalization today, are wary of how this “submit” word is to be interpreted.

In my research, I’ve come across an interesting reading of this word from Najeeb Haddad who, building on the work of others, argues that the greek word translated submit should be translated as “fit in.”6 Meaning, that one should fit into the society in which one lives understanding that on some level God orders all societies so as not to fall into chaos.

But Haddad further explains that this different connotation of “submit” has a history of being used as both a “virtue” or a “vice” in the ancient world.

Meaning, when it is used as a vice, it is best translated as “subordinate” or “submit” implying that one puts themselves in this position because while subjecting themselves they receive some kind of benefit of fame, power, or wealth they would not otherwise experience.

Whereas in the sense of a virtue, when it is used, it has the sense of fitting into the appropriate place one finds themselves in within society that God has ordered, understanding that all society and rulers can only be obeyed to the extent that they follow God’s ordered plans for a good society.

This argument may go too far, but Gaventa, Gorman and others do certainly see that “submit” here isn’t to be viewed as an overly dominant word and is indeed considered “softer” than the word used to “obey” God throughout the book of Romans.

Either way, there is a limited sense in which the Christian follows the laws of the land. The way one follows those laws, or “fits in” might be limited simply to paying taxes as Paul suggests. Similarly in our world, getting permits for renovations on a home, obeying traffic laws and similar sorts of mundane municipal responsibilities could be the extent to which this passage is supposed to function.

Whatever it means, it is clear that it should have a much more limited place in our understanding of political theology and the church’s engagement with government than the pride of place that it has typically been given.

How have you read or interpreted this passage? What have you been taught that it means? I’d be curious to hear your experience in the comments.

Romans: A Commentary, Westminster John Knox Press, 2024.

‘The Fight to Define Romans 13,’ The Atlantic, June 15, 2018.

Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans, Books 6-10, Book 9, p 224. Translated by Thomas P. Scheck

Bruce, F. F. Romans: An Introduction and Commentary. Vol. 6. Tyndale New Testament Commentaries. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1985. p 230.

See Fitzmeyer, Joseph,

Haddad, Najeeb, ‘Reassessing “Submission”: Applying the Work of Troy W. Martin to Romans 13:1-7, Biblical Research 67 (2022): 81-92.

I just finished Reading While Black for Book Club. Great discussion on this topic and many others. I appreciated McCaulley's fresh perspective on these verses. Also highly recommend!

In Reading While Black, McCaulley says (among other things) we have to hold this passage in tension with the fact that Paul gives props to Moses, who was perhaps the ultimate rebel against “the state” when he led Israel out of Egypt. I like your thoughts here. It will be interesting to see how you develop this in your paper!