The Christian and the State: A Surprising Corrective

Part 3 of 3: Mis-Reading Romans 13:1-7 With Our Modern Problems

Hello Reader! This month, I’m sharing an essay on Paul’s meaning in Romans 13:1-7 that I wrote for a recent class at Northern Seminary co-taught by Drs. Tim Gombis and Nijay Gupta in three parts.

This passage is a touchy subject, especially with its opening, “submit to the governing authorities” line that leaves Christians with a lot of questions.

This text also has a checkered past, being used by the Nazi party to endorse totalitarian rule and in apartheid South Africa. It is not without its controversy!

In this series, I hope to shed some light on what Paul is trying to do here as well as point out some modern assumptions that get imported into the text that make it harder to understand.

May 2 - I’ll share a little background and my own motivation for writing this

May 16 - For you Greek nerds, this is when we will get into the nitty-gritty of the text itself.

May 30 - I’ll offer some contextual considerations and comments for helpful interpretation

In addition to the actual text of the essay I wrote, you will see addendums, which include some added elements I did not have space to discuss in the original paper.

Welcome to Part 3!

Thank you so much for joining me on this interpretive journey.

To be honest, this series has been less popular than other posts I’ve written, which may be due to the more academic tone I’ve used; that’s understandable.

But I think this is one of the most important texts to understand in our current moment.

As a pastor in the times we live in, I felt an urgency to understand this text for myself, especially to what extent Paul expects Christians to “submit to governing authorities.”

In Part 1, we explored some helpful background information for Paul and the church in Rome, especially the social location from which he was writing and why that was important.

In Part 2, we did the more tedious work of unpacking a lot of the Greek words (not everyone’s favorite, I get it, but important for this passage in particular, as we will see today).

Here in Part 3, we will pull together the insights from the first two sections to explain what Paul wants us to do with this often confusing passage.

So here we go…

Introduction

It is perhaps never truer than with Romans 13:1-7, that we “read with our interpretive predecessors.”1

There are numerous interpretive issues brought to us by the history of the Western church. I want to discuss two of these issues here.

First, we will consider the unity of the text of Romans 13:1-7 with the surrounding writing. Specifically, Romans 12 and the rest of Romans 13. We have to read this small section in the larger context to understand its purpose.

Second, we will consider the oft-made mistake of reading “the State” into this passage and explore the problems this creates for modern readers of ancient writings.

From my observations on these two issues, I will conclude this series, contending that two things need to happen:

1) Resist trying to “make” this text do more than it is doing.

2) See this text as not only about how much or little we submit, but also about a repudiation of those using Christian faith to create antagonism in wider society.

The Unity of the Text

As already explained in the analysis of Part 2, 13:1-7 is a unified whole, especially with 12:1-21, which precedes it, and 13:8-14 after it. It is an unfortunate reality that the chapters break where they do.

Paul is particularly concerned with ensuring this vulnerable church is strengthened, and Beverly Gaventa argues that if this is the case with what precedes and follows 13:1-7, this is likely the purpose of the text at hand.

Paul was concerned for the safety of this community if they were to choose to resist paying taxes. Thus, he provides a rationale for them to continue to pay what is asked of them2 and seems to do so by echoing, in his own way, the words of Jesus in Mark 12:17.3

When reading Romans 12-13 as a unified text, it becomes clear that, to whatever extent submission to governing authorities took place, this happened while the church,

blessed those who persecuted them (12:14),

paid back evil with good (12:17),

did all they could to live at peace with everyone (12:18),

never took revenge but let God instead (12:19),

fed their enemy that was hungry and thirsty (12:20),

and conquered evil by doing good (12:21).

Offering a longer explanation as to why a Christian should pay taxes at this point follows logically. The authorities might be the very people whom the Christian community was being persecuted by.

Instead of practicing revenge as would have been expected in Roman culture, they were participating in the humble nature of Jesus by blessing them, paying back evil with good, and feeding their enemy that was hungry, for example.

Continuing into the rest of Romans 13, Paul’s command to pay taxes as part of this humble, Jesus way of ordering society, is but a small part of what a Christian truly owes: the “obligation to love one another” and to love their neighbor which ultimately fulfills God’s laws (13:8).

It is fulfilling the higher law of God, from whom all governing authorities derive their authority, that truly matters.

To put it bluntly, Paul is not encouraging docile support of all laws within a city or nation. Paul wants them to do their best to stay within the bounds of the society they are in as long as it does not violate the higher law of God.

If there is a group of people, refugees and asylum seekers for example, that are being persecuted by governing officials and their laws, Christians still have a responsibility to care for the stranger and the needy and in so doing, conquer evil by doing good.

We are not honoring God when we submit to laws that dishonor God’s higher law.

This unified reading of 13:1-7 with the surrounding text demonstrates the limitations to which the church is being commanded to submit and the category-shattering nature of the Christ event.

It is an upside-down kind of submission. Not unto docility, but unto love for the world.

Misreading “The State” in 13:1-7

Frequently, this passage has been mistakenly framed as instructions on the Church’s relationship to “the State”.4

The extent to which this happens with this text is, honestly, mind-boggling to me and is incredibly problematic.

There is no mention of such an institution in this passage.

The State is a modern construct read into the text to which Paul was not referring. That “Rome” itself is not even mentioned emphasizes this point even more.5

Instead, only “authorities” is mentioned, which, as has been observed, seems to refer to generic officials doing jobs such as tax collection.

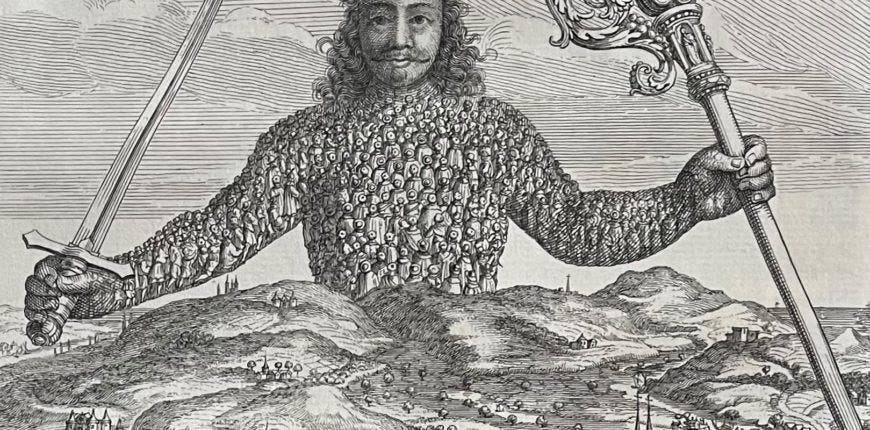

When moderns attempt to read “the State” into the text and its relationship with the Church, we are forced to interpret this passage with categories more akin to Thomas Hobbes than the Apostle Paul.

This, I contend, is a major reason why this passage has become so confusing and dangerous because it requires us to navigate a set of relationships to which the text does not speak.

Hobbes, in his massively influential book, Leviathan, shaped a vision of the modern Nation-State as a replacement for the church’s role to discern God’s will for living well in society.

This resulted in his conclusion that unquestioning uniformity and loyalty to the Sovereign was the only way to preserve order in society.6

Living in the aftermath of a particularly brutal English civil war, Hobbes felt that unquestioning loyalty where all conformed to the will of the head, was necessary to have peace.

Even the church could not be trusted to unify society.

It is important to note that this was a time in history that operated within a Christendom framework.

This framework assumed Church-State interdependence and did not have room for the possibility of the Church functioning as an alternative society in the midst of the world.

So naturally, in Hobbes’ mind, there would be a Christian Sovereign and a Christian State.

We are all Christians, right?

This created a complicated web of loyalty that blurred the lines between Christian faithfulness and State Allegiance.

Therefore, anytime the concept of “the State” is invoked even today, we instantly are required to wrestle with the blurred line that we owe in large part to him.

This reading requires that the State be a God given institution that demands loyalty to ensure peace. Note, this is decidedly different from what the text of 13:1-7 says, which is that governing officials are God’s servants, not that “the State” is instituted by God as Hobbes would argue.

This is why we struggle so much in our interpretation of this passage.

By reading “the State” into Romans 13:1-7, one immediately imports these Hobbesian categories of conformity to the State and creates an unnecessary dance around when we do and do not obey the State and where the “line” is for Christians to begin to dissent.

Given the context of the surrounding passage, this is clearly not confusing for Paul.

One pays the tax they are being asked to pay as well as loving and caring for all people, and owing to everyone the debt of love to one’s neighbor (13:8-9).

When this mistake is made, at worst, this passage becomes open to gross over-interpretation and coercion as was witnessed in Nazi Germany and in South Africa’s apartheid.7

At best, it forces one to negotiate a set of relationships between church and government which are beyond the scope of the passage, leaving us confused and unsettled.

Conclusion: A Surprising Corrective

In light of these interpretive considerations, I believe that the scope of this passage’s original intent is extremely limited to the immediate issue of paying taxes without resistance.8

Since the Jewish believers are returning and reintegrating with the gentiles, a reminder of how the Christ Event shapes their interactions toward the broader world, including paying their taxes to governing authorities, is the extent of Paul’s intended instruction.

This has a helpful but limited application in our own day.

We could gather that it is important to submit to local governing authorities by paying our own taxes as well as obeying traffic laws, applying for permits to do work on a home or church building, and following local health ordinances related to septic and sewage disposal.

Not doing so (wrong doing) could result in large fines, and resistance to such laws does nothing to demonstrate one’s allegiance to Jesus.

This offers a crucial corrective to those who believe they need to take a stand on issues vital to their Christian faith.

There needs to be differentiation between not submitting to laws because they violate our ability to love our neighbor, and not submitting to laws because we want to show how “Christian” we are.

This was exactly what Paul was concerned about with the Jewish communities’ return to Rome. And this is the same situation Jesus faced when presented with a seemingly impossible question of whether they should pay taxes to Caesar or not.

The surprising corrective I find in Romans 13:1-7 is that we are not to take an antagonistic stand.

Sean Feucht’s “Let Us Worship” rallies, in some ways, serve as a poignant example of this. Originally, Feucht organized these worship events to defy quarantine and gathering size orders during COVID.

The claim was that this was persecution against the church’s right in the United States to gather and worship freely.

However, it was not necessary for one to organize mass gatherings in order to demonstrate faithfulness to Jesus. In fact, Paul follows the point of submitting to authorities by paying taxes saying, “the one who loves his neighbor fulfills the law” (13:8).

If Feucht truly believed that these mass gatherings were necessary to be a faithful Christian, I would encourage a re-examination of his own ecclesiology.

By all means, take a stand to love one another and fulfill God’s law, but if taking a stand will not result in love, but rather proving a point, stop!

This means that when the law of love is violated by society and governing officials, we as Christians have no obligation to uphold and submit to those laws and governing leaders.

Further still, if the law of love is not being violated in the rulings of governing officials, we have no standing to resist those governing authorities.

The inverse is also true. This was a text directed to a church community to instruct their interaction towards the world, not a text directed to governing officials’ interaction towards the Church.

Any appeal by governing officials based on this text, that Christians should offer blind loyalty to any government, is a gross misuse of Paul’s instructions.

Thank you for reading!

If this series has been helpful, please let me know what you think or share this article with someone who needs it.

Gaventa, Romans: A Commentary, 452.

Gaventa, Romans: A Commentary, 453.

Dunn, Romans 9-16, 768.

See e.g. F. F. Bruce, Romans : An Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale New Testament commentaries; Volume 6 (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic, 1985), 230.

Fitzmyer, Romans, 662.

See Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, First Avenue Classics (Minneapolis, Minnesota: First Avenue Editions, 2018), Part 3.

Gaventa, Romans: A Commentary, 453.

Gorman, Romans : A Theological and Pastoral Commentary, 254–255.